Where Did Mexico’s Blacks Go?

By Steve Sailer

Where did Mexico’s blacks go?

The nearly complete absorption of Mexico’s identifiably African people offers an intriguing contrast to the persistence of a rather distinct black race in the United States.

Most Americans, and even many Mexicans, don’t realize that a significant fraction of the Mexican population once looked markedly African. At least 200,000 black slaves were imported into Mexico from Africa. By 1810, Mexicans who were considered at least part-African numbered around a half million, or more than 10 percent of the population.

Mexican music, for example, has deep roots in West Africa. “La Bamba,” the famous Mexican folk song that was given a rock beat by Ritchie Valens and a classic interpretation by Los Lobos, has been traced back to the Bamba district of Angola.

What’s especially ironic about Mexico’s “racial amnesia” — a term coined by African-American historian Ted Vincent — is that during Mexico’s first century of independence, more than a few of its most famous leaders were visibly part black.

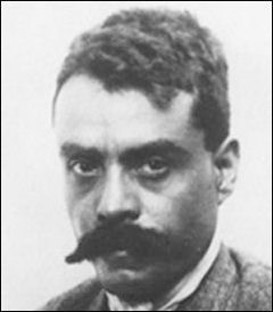

Emiliano Zapata (pictured left) was perhaps the noblest figure in 20th century Mexican politics, a peasant revolutionary still beloved as a martyred man of the people. Although Marlon Brando played him in the 1952 movie “Viva Zapata!” the best-known photograph of the illiterate idealist shows him with clearly part-African hair. His village had long been home to many descendents of freed slaves.

Emiliano Zapata (pictured left) was perhaps the noblest figure in 20th century Mexican politics, a peasant revolutionary still beloved as a martyred man of the people. Although Marlon Brando played him in the 1952 movie “Viva Zapata!” the best-known photograph of the illiterate idealist shows him with clearly part-African hair. His village had long been home to many descendents of freed slaves.

Similarly, Vicente Guerrero, a leading general in the Mexican War of Independence and the new nation’s second president, appears from his portraits and his nickname to have been part black.

Perhaps African-Mexicans were so often leading the revolutionary vanguard because they were even more oppressed by law than Mexico’s Indians. Back in the 16th century, the great Spanish Bishop Bartolome de las Casas, the first modern human rights activist, in the sense of battling for justice for another race, persuaded the King of Spain to ban the enslavement of Indians, at least nominally. Yet, bondage for Africans remained legal until “El Negro Guerrero” officially abolished it in 1829. It had largely withered out before then, however.

The apparent assimilation of Mexico’s ex-slaves into the overall gene pool is in marked contrast to America’s experience, where the black race has remained relatively distinct. In the average self-declared white American’s family tree, there is only the equivalent of one black out of every 128 ancestors, according to the ongoing research of molecular anthropologist Mark D. Shriver of Penn State University and his colleagues.

In fact, Mexico even differs from the rest of Latin America, where distinct black populations remain genetically unassimilated. “Mexico is unique in this regard,” commented population geneticist Ricardo M. Cerda-Flores of the Mexico’s Autonomous University in Nuevo Leon.

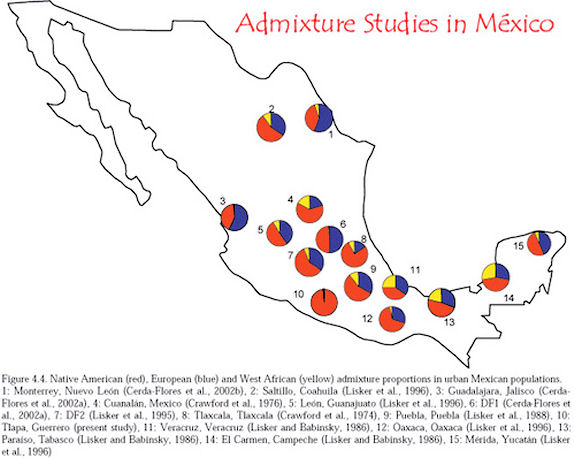

Cerda-Flores’ team found that a sample of Mexicans living around Monterrey in Northeast Mexico averaged around 5 percent African by ancestry, according to its genetic markers. In other words, if you could accurately trace the typical family tree back until before the first Spaniards and their African slaves arrived in Mexico in 1519, you would find that about one out of twenty of the subjects’ forebears were Africans.

Cerda-Flores and his colleagues also examined the DNA of Mexican-Americans in Texas, who came out as about 6 percent black. Other studies of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans by molecular anthropologists have come up with black admixture rates ranging from 3 percent to 8 percent.

By way of contrast, this appears to be, very roughly, something like half of the black ancestry level of the overall American population, as implied by Shriver’s studies. Of course, most of the African ancestors of Americans are visibly concentrated among African-Americans, who average 82 percent to 83 percent black, according to Shriver. Among Mexicans, however, African genes appeared to be spread more broadly and evenly.

Nevertheless, the official ideology of Mexico has been that the Mexicans are simply a “mestizo” people — a mixture of Spaniards and Indians — officially referred to as “La Raza” or “The Race.” Since 1928, Mexico has celebrated Oct. 12 as “The Day of The Race.” On Oct. 12, 1946, Mexican politician José Vasconcelos famously declared mestizos to be “the cosmic race.”

African-American anthropologist Bobby Vaughn wrote, “Issues of race have been so colored by Mexico’s preoccupation with ‘the Indian question’ that the Afro-Mexican experience tends to blend almost invisibly into the background, even to Afro-Mexicans themselves. Mexico’s official narratives … leave Afro-Mexicans outside of the national consciousness.”

That’s because Mexico’s national ideology centers on “the belief that contemporary Mexico is a kind of ‘perfect blend’ of both Spanish and Indian heritages, and that this synthesis is at the heart of what it means to be Mexican.”

Socially, Mexico does not have any kind of “color line,” in contrast to the United States, where “one drop of African blood” frequently categorizes a person as “black.” For example, Oscar-winning actress Halle Berry’s white mother raised Halle to think of herself as black, even though her African-American father abandoned the family when she was quite young. Those kind of sharp-edged racial categories seldom exist in Latin American countries.

In reality, Mexico’s white-Indian racial blending is far less complete than Mexico’s political orthodoxy would make it appear. What Mexico does have instead of a color line is a “color continuum.” There are no sharp racial divides, yet the rule for social prestige remains “the whiter the better.” For example, the stars of Mexican television are almost completely European. In fact, the actresses on Mexican “telenovelas” tend to be blonder than the ones on American soap operas.

Mexico’s elites are much whiter looking than its working class. At 6’5″ tall, President Vicente Fox stands roughly a head taller than the average Mexican man. Fox’s paternal grandfather was an Irish-American born in Cincinnati.

There remain in dire poverty millions of virtually pureblooded Indian peasants, who speak the same Indian languages as their ancestors did before 1492.

This ideological assumption that all Mexicans are mestizo can lead to some amusing conundrums. For example, Luis Echeverria, president from 1970-1976, saw himself as the natural leader of the nonwhite Third World. The problem was that he, like most Mexican presidents, appeared to be pure white. So, he spent many hours under sun lamps, trying to tan himself into the Third World.

While it’s easy to scoff at this “mestizo myth” as propaganda put out by the mostly white ruling class to keep the brown lower classes from noticing Mexico’s racial hierarchy, its usefulness at maintaining the peace should not be despised. In recent decades, Mexico has suffered much less from racial violence than nearby Guatemala or more distant Peru. During the ’80s in both of those countries, where attitudes of white superiority are more blatant than in Mexico, oppressed Indians joined Marxist intellectuals in guerilla wars against the white ruling class.

The Mexican populace’s African “third root” is occasionally honored, but Mexican officials have generally ignored it. University of Minnesota demographer Robert McCaa wrote, “Afro-Mexicans, who numbered one-half million in 1810, more or less vanished, thoroughly intermingled and unidentifiable by 1895 if the official discourse is accepted at face value.”

That discourse should be viewed skeptically. It’s unlikely that African racial characteristics had become so blended in by 1895 that they had actually vanished. Yet, since then, black genes appear to have been so broadly distributed around the population that few Mexican individuals stand out today as notably black.

In fact, the black contribution to Mexico’s “cosmic race” has been so forgotten that in last November’s race for governor of the state of Michoacán, Alfredo Anaya of the former ruling party PRI hammered away at his opponent Lázaro Cárdenas, the scion of Mexico’s most famous leftist dynasty, for having a part-black Cuban wife and son.

Anaya argued, “There is a great feeling that we want to be governed by our own race, by our own people.”

One of his supporters said, “It’s one thing to be brown. The black race is something different.”

Ultimately, this strategy failed, as Anaya lost. Still, he came within five percentage points of beating the son of Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, the man who is widely believed to have been cheated out of Mexico’s presidency in 1988 by massive PRI vote fraud. Further, this Lázaro Cárdenas is the grandson of the Lázaro Cárdenas, Mexico’s most popular president, who is still adored for triumphing over the United States by nationalizing American-owned oil companies in 1938. So, considering the vast name recognition enjoyed by Cardenas, Anaya’s pro-mestizo and anti-black ploy cannot be dismissed as wholly ineffectual.

By 2001, after generations of intermarriage, no more than 1 percent of the Mexican population is said to be identifiably African. Most of the remaining Afro-Mexicans are concentrated in the humid coastal regions, rather than the cooler highlands or dry northern desert.

There are self-consciously Afro-Mexican communities on the Gulf of Mexico near Vera Cruz, where the slave ships docked. There are heavily black villages on the Costa Chica on the Pacific, although the residents tend to see themselves as simply Mexicans with dark skins. One confusing factor is that Mexico also imported slaves from across the Pacific, including some African-looking New Guineans and also Negritos from the Philippines.

Life can be difficult for black Mexicans, because they are often assumed to be illegal immigrants from elsewhere in Latin America, such as Panama. The Mexican police often treat illegal aliens harshly.

Mexico’s obliviousness to its black roots is slowly changing. An Afro-Mexican Museum recently opened south of Acapulco in Cuajinicuilapa in the state of Guerrero, which is named after the Afro-Mestizo second president.

So, what happened to the Afro-Mexicans who made up one tenth of the population in 1810?

The massive importation of East African slaves into the Middle East has not left much of a visible trace there either, although Prince Bandar, the Saudi Arabian ambassador to America, is clearly part black. Historian Bernard Lewis attributes this lack of blacks to the tendency in the Islamic world to castrate male slaves and work both sexes to death.

In contrast, the Mexican experience appears to have been much more benign. According to Cerda-Flores, intermarriage continued steadily until African genes had widely diffused into the population.

It’s often argued these days that race is purely a “social construct.” This view often puzzles geneticists, such as the forensic anthropologists who are employed by the police to examine hairs left at crime scenes and determine the race of suspects from their DNA.

Yet, there is a definite sense in which societies construct their own genetic makeups. America’s color line and “one drop” rule have kept the genes of black Africans relatively isolated. In contrast, Mexico’s color continuum and openness to interracial marriage have spread them so widely that there are few conspicuously black Mexicans left.

Article Source: Steve Sailer Blog

Related:

Mexico’s population today: 9 percent White, 30 percent Indian and 60 percent Mestizo

http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/geos/mx.html

Alta-California Racial Census of 1790