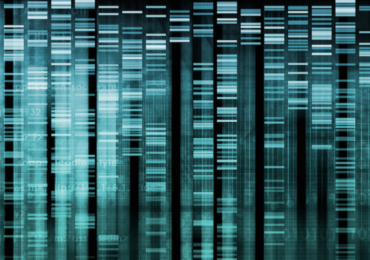

A new genetic study of Jews in North Africa has “confirmed the biological basis of Judaism,” according to its Jewish author, professor Harry Ostrer.

A new genetic study of Jews in North Africa has “confirmed the biological basis of Judaism,” according to its Jewish author, professor Harry Ostrer.

Professor Ostrer, of the departments of pathology, genetics and pediatrics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine at New York’s Yeshiva University, came to prominence a short while ago with the publication of his book Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People.

His latest study, published online in the Proceedings of the US National Academy of Sciences, analyzed the genetic make-up of 509 Jews from 15 populations compared with genetic data on 114 individuals from seven North African non-Jewish populations.

North African Jews are the second largest Jewish Diaspora group. Until now, how they are related to each other, to other Diaspora groups and to their non-Jewish North African neighbors had not been well defined.

The study also included members of Jewish communities in Ethiopia, Yemen and Georgia.

“Our new findings define North African Jews, complete the overall population structure for the various groups of the Jewish Diaspora and enhance the case for a biological basis for Jewishness,” said professor Ostrer.

In a previous genetic analysis, the researchers showed that modern-day Sephardi (Greek and Turkish), Ashkenazi (Eastern European) and Mizrahi (Iranian, Iraqi and Syrian) Jews originating in Europe and the Middle East are more related to each other than to their contemporary non-Jewish neighbors, with each group forming its own cluster within the larger Jewish population.

In addition, each group showed Middle-Eastern ancestry and varying degrees of mixing with surrounding populations.

North African Jews exhibited a high degree of endogamy – a term that refers to marriage within their own religious and cultural group – in accordance with their community’s custom.

Two major subgroups within this overall population were identified – Moroccan/Algerian Jews and Djerban (Tunisian)/Libyan Jews.

The two subgroups varied in their degree of European mixture, with Moroccan/Algerian Jews tending to be more related to Europeans, which most likely resulted from the expulsion of Sephardi Jews from Spain during the Inquisition starting in 1492.

Ethiopian and Yemenite Jewish populations also formed distinctive genetically linked clusters, as did Georgian Jews.

Compared to the variation of the worldwide population, Jewish communities were quite different. They mostly married among themselves, with not enough mixing with the non-Jewish group to make it possible to separate the DNA.

There is a shared Jewish ancestry of Near East origin among Ashkenazim and other Jews who had been separated for thousands of years.