Are Jews a religion or race? This is the age-old question that medical geneticist Harry Ostrer tackles in his concise but informative book, Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People.

Are Jews a religion or race? This is the age-old question that medical geneticist Harry Ostrer tackles in his concise but informative book, Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People.

As Professor of Pathology and Genetics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University and Director of Genetic and Genomic Testing at Montefiore Medical Center, as well as former Director of the Human Genetics Program at New York University’s School of Medicine, Ostrer has devoted much of his career to unraveling the DNA sequencing of recessive genetic disorders common among Jews, such as Tay-Sachs and Gaucher disease. After two decades of medical research, he explains that Jews share more than religious and cultural traditions — a common biological bond links Jews throughout the Diaspora.

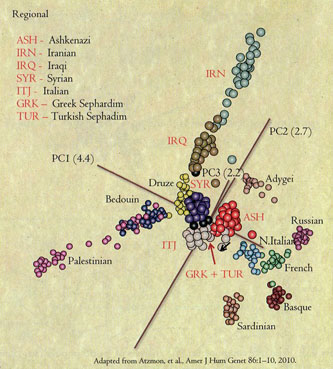

This body of work has led Ostrer to conclude that Jews are genetically related worldwide. Three millennia of selective breeding have created a distinct population with unique racial characteristics. Within this broad isolated population, diverse ethnic tribes formed and branched out. Mutual genes serve as the ancestral linkage between major Jewish tribes: Ashkenazi (who are related to one another on average as fifth cousins), Sephardic, Eurasian Khazars, Middle Eastern, and Mizrahi or African Jews.

Legacy is a slim book that incorporates history, natural selection, population genetics, evolutionary psychology, and contemporary medical findings. The author’s quest for the basis of Jewish origins and identity forms the basic storyline of Legacy. Each chapter highlights various aspects of Jewish ancestry: physical measurements and characteristics, DNA studies, blood groupings, genealogical evidence, tribal lineage, physical and psychological traits, and, finally, the crux of Jewish identity. The result is an informative overview of 25 years of detective work unraveling the genetic kinship of Jews.

Ostrer explains how technological advances in genomics allow researchers to tease out population differences and migration patterns to the degree that it is possible to identify genetic subclusters in diverse populations. Research developments in the past decade have boosted the Jewish HapMap Project, the major research endeavor the author has spearheaded with his colleagues.

In utilizing these new research tools, geneticists have been able to trace the degree of genetic similarity across different Jewish groups in areas where the populations are genetically heterogeneous. Ostrer points out,

The Jewish HapMap Project demonstrated in exquisite detail what had been conjectured for a century. Jewish populations from the major Jewish Diaspora groups — Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Mizrahi — form a distinctive population cluster that is closely related to Semitic and European populations. Within this larger Jewish cluster, each of the Jewish populations formed its own subcluster. Each group demonstrated Semitic ancestry and had variable degrees of admixture with European populations.

In his concluding chapter on Jewish “Identity,” Ostrer summarizes the central point of his work:

The evidence for biological Jewishness has become incontrovertible. The answer to Jacobs’ 1899 question, “Are Jews Jews?” would seem to be an emphatic yes. As noted earlier, a study by Goldstein and his coworkers demonstrated that it was possible to predict full Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry accurately and with a somewhat lesser degree of certainty for people with one, two, or three Jewish grandparents. The Jewish HapMap Project has extended these findings to people who come from virtually all other Jewish groups, each group representing a genetic cluster that can be defined as a predominant pattern of inheritance that includes a large number of genetic markers. The findings are based on the fact that segments of the genome tend to be shared at a higher frequency among members of different Jewish groups. This degree of shared genetic segments is greater among Jews than between Jews and non-Jews. So Jewishness at a genetic level can be characterized as a tapestry with the threads represented as shared segments of DNA and no single thread required for composition of the tapestry.

The fate of the Khazars — a semi-nomadic people of Central Asian Turkic origin in the area of Southern Russia, which was ruled by a succession of Jewish kings from essentially the eighth to the eleventh century — “has been the subject of much speculation,” as Ostrer notes, not to mention a source of contention among Jewish scholars.

Ostrer briefly mentions the Khazar controversy. After skimming through the history of the Khazars, he believes the findings from the Jewish HapMap Project refute “the theories that Ashkenazi Jews are the descendants of converted Khazars or Slavs.”