This heart gripping piece of history about The Battle of Blood River as related by Deirdre Fields must be told to the world, as at this moment again we are faced by overwhelming odds:

This heart gripping piece of history about The Battle of Blood River as related by Deirdre Fields must be told to the world, as at this moment again we are faced by overwhelming odds:

The Battle of Blood River

It Was Boer versus Zulu in a Life & Death Struggle For the Survival of the ‘White Africans’

By Deirdre Fields — MP3

The 16th of December 2008 marked the 170th anniversary of the Battle of Blood River, an event that lies at the heart of Afrikaner nationalism. It is a story of courage, determination, sacrifice, suffering and of undaunted faith in God. It even has mystical aspects. But it is a battle that could have spelled the fate of the Boer nation—perhaps even should have been their end—but miraculously was not. It enabled an entire saga of the whites of South Africa to unfold. Here, then, is the remarkable saga of the Battle of Blood River.

The Boers climbed “Execution Hill” (Hlomo Amabutu) in the hot, subtropical, Natal sun; the stench of rotting flesh filled their nostrils. This had been the Zulu King Dingaan’s execution site—and many had been the executions he had ordered. Thousands had found their tortured, final resting place here. Mostly, executions were conducted with the aid of a sangoma or witchdoctor, who would conduct “smelling out” ceremonies, during which he would claim to sniff out those people who were evil, wizards, or plotting some mischief against the chief.

Sometimes he would “smell out” hundreds at a time. Then they would be taken to Hlomo Amabutu to be executed, their bodies left for the vultures (which Dingaan affectionately referred to as his “children”) to feed upon. Holding their noses, the Boers picked their way over countless bones and bodies. Vultures rose to the air reluctantly, squawking their protest, their stomachs distended—with rotting human flesh.

At last, the Boers recognized the remains of the bodies of the white men: Piet Retief and his party, whom Dingaan had murdered treacherously and cruelly.

The Zulus had held Retief and forced him to watch, as one by one, his comrades, and finally his own teenage son were murdered before his eyes—bludgeoned with a knobkerrie (war club) or sliced up with an assegai (Zulu spear). When it was all over, Retief’s heart and liver had been cut out and presented to Dingaan. But what was that? Beside Retief’s body lay a leather pouch. Inside lay that precious treaty he had signed with Dingaan, granting the Boers all the land between the Tugela and Umzimvubu rivers. Here was proof that the Voortrekkers had won the land two ways: by treaty and by battle.

But something was strange—here, in this place of iniquity, where the vultures gorged on their accustomed diet of the flesh of black victims; as though kept at bay by a hidden hand, they had not touched the bodies of the Voortrekkers. Looking at the treaty, Andries Pretorius thought back on the events that had led up to this moment—back to the cape, in the years between 1835 and 1838.

The British had no time for the Dutch-Afrikaans speaking, freedom-loving Boers, and they used the race issue against the Boers to hinder and control them, to the extent that they felt neither secure nor free to conduct their lives in such a way as to ensure their own security, and they could see no future for their children. As the British government had grown in strength, British authority and military presence had became increasingly heavy-handed in the region, and with this came the curtailment of the (Boer) burgher commandos.

Another ongoing problem was created by homeless bands of Hottentots and former slaves—Malays and some West Africans—brought to the cape by the Dutch East India Company. These roving gangs presented a real risk to the safety of whites and more civilized blacks.

Furthermore, missionary societies, mainly acting as agents for the British government, had set up a type of “ACLU,” [American Civil Liberties Union] which made it their business to collect any and all minor anti-Boer grievances and reports of maltreatment, and champion them through the courts.

In court, it seemed that the animist[1] complainants were automatically believed—they who had no value system that deterred lying, and they who had nothing to lose in making such claims and everything to win. Many spurious cases were prosecuted against the Boers, who were thus persecuted in the courts.

The infamous “Ordinance 50” set out the basis for a raceless society which spelled, then, as now, the end of cultural and ethnic integrity for all races and the extinction of the white race. Their descendants understand this intimately. Since 1994 they have been the victims of an ongoing attempt launched by the Xhosa-dominated[2] government to genocide whites in South Africa. The conditions of whites today is strikingly similar to those of the Boers on the cape in the 19th-century.

The British authorities either could not or would not give the Eastern frontier Boers protection against the constant raids by the Xhosa from across the Fish River. The Xhosa would plunder their cattle and attack Boer homes, often murdering the occupants and burning their houses, before Boer commandos could mobilize. During the Sixth Frontier War, 40 farmers were murdered, 416 homesteads burned and thousands of horses, cattle and sheep stolen. The British authorities pursued a policy of appeasement toward the Xhosa.

Unable to tolerate the oppressive British rule any longer, from 1835 onward, some 15,000 Boer families packed up the few possessions they could fit into their canvas-covered wagons and set off for the interior, hoping there to find land, freedom, and self-determination, whilst preserving the integrity of their people—that essential pre-requisite for maintaining one’s unique cultural identity. They could speak their own language, worship their God and live according to their own culture, without interference. This Great Trek was the calling out of the people who would form the Boer nation. [See TBR’s “The Great Trek of the Boers,” the cover story of the November 1997 issue.—Ed.]

These were passionately independent, freedom-loving people summed up what it meant to be a Boer decades later in their anthem (as translated into English): “slaves of the Almighty, but before all others, free and uncompromised.”

These were principled people rather than materialistic: The cape had been so built up that it was known as the “fairest cape in all the world,” and “Little Paris” thanks to the efforts of the Boers.

But they left behind their beautiful “Cape Dutch” homes and farms, to travel into the unknown hinterland, with nothing but their pots and pans and the few small items they could carry in their wagons. Those unable to make the sacrifice for their principles, or who did not share these principles, stayed behind. Thus was the Boer nation born—in the spirit of self-sacrifice, with a big Bible in one hand and a gun in the other. The events of the Great Trek would provide a common history of hardship and sacrifice, and a belief in divine intervention that would forge the Boers indelibly into a distinct national identity.

For the first Voortrekkers, things did not go well: Jan van Rensburg’s small group, which left in 1835, was ambushed by blacks on the high veldt and massacred. Louis Trichardt’s party survived attacks by blacks, only to be vanquished by malaria.

The few survivors struggled on to Lorenzo Marques, Mozambique, where the friendly Portuguese put them on a ship returning to the cape. This disaster might have deterred other treks in a more complacent people, but the Boers in the cape were unable to meet the dangers that faced them on their own terms, because the British laws effectively tied their hands. They were determined to gain self-determination.

Of French Huguenot ancestry, Retief was an educated man, of a refined and intelligent character. His experience fighting the Xhosa and his leadership role in mediations with the British had developed in him just the skills necessary to lead such a trek. Retief led his party across the Orange River, and out of British-held territory to Thaba Nchu, where they met up with other parties of Voortrekkers who had left earlier. Retief was promptly elected as the leader of the combined group. Retief led the largest group of Trekkers across the formidable Drakensberg Mountains (Dragon Mountains) into Natal, while yet others crossed the Vaal River into the Transvaal or remained in what was to become the Orange Free State.

Previously, in return for 49 cattle and Boer protection against the Matabele chief Mzilikazi (a renegade Zulu captain), the black leader Makwena had granted Hendrik Potgieter’s party the land between the Vet and Vaal rivers. When, in 1836 Mzilikazi attacked, Potgieter’s commando brigade succeeded in driving Mzilikazi and his Matabele (Ndebele) from the western Transvaal into what is now Zimbabwe, where they have remained to this day.

For the Retief Trek, crossing the formidable Drakensberg Mountains in itself was an almost superhuman feat, requiring an indomitable determination, resilience, and perseverance not to mention an optimistic, adventurous spirit. These intrepid qualities were required of even the children and women, for the ordeal was easy on none, and it became indelibly etched into the Boer psyche.

Tottering over near-vertical inclines, they ascended the Drakensberg, and on the other side, they descended often near vertical declines, requiring that the wheels be removed from the wagons, and saplings tied in their place; while the men would hold fast onto ropes at the front of the wagons, to prevent them from running over the oxen—making their laborious descent, almost on their knees; or careening to their destruction far below. There were no stores en route, and Voortrekkers had to be resourceful in creating all of their own commodities, from making their own soap, candles, bullets, wagon parts, shoes, clothes, makeshift ovens—from termite mounds—to developing their own medical cures, “Boererat” (Boer remedies), which drew heavily on the knowledge of nature and the use of local herbs.

As they left the cape, they started reading their Bibles at the point where God leads the children of Israel out of bondage in Egypt and leads them to the land of milk and honey in Canaan, the Promised Land. Naturally, they identified strongly. When they saw the green lands that lay before them, as they surmounted the Drakensberg, they could not be blamed for thinking that they too, had reached the Promised Land, and they called it Blydevooruitzicht— “Happy Prospects.”

Leaving the bulk of his party encamped along the Bloukrans River, Retief led a party of some 60 men and teenage boys to negotiate for land with Dingaan, the chief or king, at his kraal [enclosure], Umgungundlovu (“Place of the Elephant,” meaning Dingaan himself). Dingaan promised Retief and his trekkers that if they could recover the cattle a local chief had stolen from him, he would grant them land. With little difficulty, the Boers recovered the cattle, and on February 2, 1837, they arrived at Umgungundlovu with the some 7,000 retrieved cattle.

On February 5, Dingaan and Retief signed a treaty granting the Boers the land between the Tugela and the Umzimvubu rivers in Natal. (Natal was occupied at the time by the warlike Zulu tribe, like the Xhosa, part of the Nguni people, a branch of the Bantus who originated in the Uganda area.) Dingaan signed with an “X.” During the ceremony, a little Zulu child knelt at Dingaan’s side, with his hands cupped. At intervals, Dingaan would spit into his hands, and the boy would rub the spittle into his belly, praising the king. The honor was greatly coveted. Festivities followed the signing of the agreement. The following day, February 6, the Boers rose before daybreak to return to Bloukrans, where the rest of the trek party awaited them.

Just then, a messenger arrived from Dingaan, inviting Retief and his party to meet once more with the king, before they left. Retief and his trekkers, as well as two Englishmen from Port Natal, were persuaded to unwisely leave their weapons outside the kraal, as a mark of respect to the Zulu king. Offering them some sorghum beer, Dingaan toasted their friendship, attested to by the signed treaty Retief carried in his bag.

Then Dingaan commanded two of his impis (regiments) to entertain them by dancing. For some 15 minutes the warriors danced, shouted and made feinting movements with their spears. Advancing three steps and retreating two—they advanced toward the Boers. Suddenly, Dingaan arose shouting “kill the white wizards,” and immediately some 2,000 Zulus fell upon the unsuspecting Boers.

Some leaped to their feet, drawing their small hunting knives, but they were no match for the numbers and spears of the Zulu warriors. Feet trailing, they were dragged off to a hill next to Umgungundlovu, called Hlomo Amabutu, “the Hill of Execution,” there to be savagely murdered, one by one—where Andries Pretorius and the victors of Blood River would eventually find them.

About two hours after Retief’s heart and liver had been presented to Dingaan, his impis, under the captains Ndlela and Dambuza, set off to massacre the rest of the Boer party, who were camped out at Bloukrans, a considerable distance from Umgungundlovu; chanting, “We will go and kill the white dogs.” The English missionary, Francis Owen and an American, William Wood, witnessed the murder from Owen’s hut overlooking Hlomo Amabutu. Fearful for their own lives, they fled several days later for Port Natal.

Not suspecting any treachery, the Boers had not formed their wagons into a defensive circle (laager), but were camped out in groups of varying sizes. As they slept on the night of February 16, 1838, the Zulu army of some 10,000 attacked: The Liebenberg family was slaughtered in their beds. Having been left for dead, along with his murdered wife, mother, and sisters, a badly wounded Daniel Bezuidenhout managed to mount his horse and ride to warn other camps.

It was a bloody massacre: the Zulus were said to have snatched up babies, thrown them into the air and impaled them upon their short thrusting spears or dashed their heads on rocks. One man grabbed his baby daughter and ran for miles through the bush, clutching his child to his chest, only to find that she had already been murdered while still in her crib. One woman, having survived the initial onslaught, was seeking her opportunity to warn the others, when she was surprised by some Zulus, returning from their bloody pastime.

Trying to crawl into a wagon, her leg was still protruding as they came in sight of her. She lay motionless, feigning death. As they passed her by, each Zulu stabbed her leg. To flinch or cry out would have meant certain death so, with incredible will power, she managed to remain absolutely motionless, as tens of Zulus stabbed that exposed leg—and survived to tell of it. At last, some of the larger camps managed to draw their wagons into a laager, and the Zulus were fended off.

The senseless brutality of the Zulus impressed itself upon all. The body of Johanna van der Merwe was found to have been stabbed 21 times and Catherina Prinsloo 17 times. Elizabeth Smit lay with her three-day-old baby beside her—her breast hacked off. Anna Elizabeth Steenkamp’s diary describes the gory scene of a wagon filled with the corpses of 50 people, mostly children, all of whom had been hacked apart, their blood drenching the wagon. Altogether, 41 men, 56 women and 185 children had been murdered. Together with the Retief party, more than half of the Boer party in Natal had been massacred.

So, the Voortrekkers named the place Weenen, or “Weeping,” the name it is called by still, though the Black African National Congress government seeks to erase all such reminders of the Boer presence in South Africa, and how they watered the ground with their blood, and still do. Leaving their bloody handiwork at Bloukrans, the Zulus turned on the British trading settlement of Port Natal, seeking to exterminate the whites there too. Some Englishmen from Port Natal, including Thomas Halstead and George Biggar, had been murdered along with Retief’s party.

Wishing to avenge the deaths of their friends, the British set out to meet the Zulus, but only four Englishmen and 500 displaced Zulus (refugees from Dingaan) escaped to Port Natal. The English eventually took refuge on a ship in port, leaving the Zulu refugees to face Dingaan’s forces. Other Boer parties came to the aid of the Boers at Weenen but were ambushed at the Battle of Italeni.

Pretorius was a successful farmer from Graaff Reinet—an area that along with Swellendam, in opposition to the autocratic rule of the Dutch India Company, had declared itself an independent republic in 1795—before the British had occupied the Cape, though the British had reversed this the next year when they occupied the Cape during the Napoleonic wars. Many Voortrekkers hailed from this area. Pretorius’s trekkers arrived in Natal in November 1838. He was elected commandant general by the Natal Boers.

Pretorius swiftly organized a commando group of some 464 men. He would not attack the Zulus, but waited for them to attack him. First, Sarel Celliers, the pastor, led the Boers in taking an oath to Almighty God, that if He would deliver them from the Zulus and grant them victory, then forever more, they and their descendants would celebrate the day as a sacred day and celebrate it as if it “were a Sabbath.” Then, on December 15, as his scouts reported a large Zulu army in the area, Pretorius chose the site of his camp.

He formed a laager of 64 wagons into the shape of a capital “D”: the straight side ran along a deep donga or ditch which extended for some distance at a 90 degree angle to the Ncome River; the lower part of the “D” ran parallel with the Ncome, and the rest of the rounded part faced the northwest, where there were no natural defenses. The two muzzle-loading canons were positioned in openings between the wagons, while 900 oxen and about 500 horses were penned up in the center of the laager. The motto of the Boers has ever been “Boer maak ‘n plan” (“a Boer makes a plan”), and they plugged the spaces between and under the wagons with thorn bushes, which worked like barbed wire, to bar the entry of the Zulus into the laager. They also lined the donga with thorn bushes.

As it grew dark and a mist descended, the Boers hung their lanterns on the ends of their long whips, and secured them on the wagons, so that the lights shown from the wagons. To the Zulus, creeping up for a surprise attack under the cover of dark, it appeared that a halo of light hovered over the laager, protecting the Boers. “Be witched! Be witched!” they screamed as they fled in terror, leaving the Boers safe for the night.

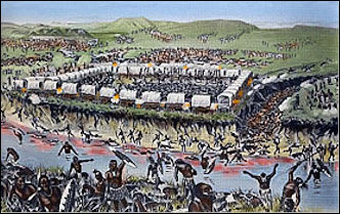

The Zulu attack came at dawn on December 16, 1838. Looking out on the veldt before them, the Boers were greeted by a seething black mass of between 15,000 and 20,000 Zulu warriors, chanting and stamping their feet in a war dance, working themselves into a killing frenzy. The sight and sound were enough to send chills through the stoutest of hearts. They had no desire to replay the events of the massacre at Weenen.

Heavily outnumbered as they were, the Boers needed to hold their fire until they were sure it would count. At the first burst of fire, the Zulus fell in the hundreds, and at every successive round, their corpses stacked up.

The successive waves of spears thrown by the Zulus came hurtling through the air like a black rain, but miraculously, throughout the battle, they caused no deaths at all. Inside the laager, the air grew blue with smoke. The Boers could hardly see their hands before them. Fortunately, the Zulus retreated out of range of the rifles, allowing the guns to cool and the air to clear before a second charge. Again and again they charged, swarming into the donga and through the river, and again and again the Boers shot into their midst, taking a heavy toll.

The Boers used their two cannon to maximum effect, at one stage aiming one as far as possible into the rear lines, and the other into the center of the front lines. Attacking en masse, the Zulus crossing the river were shot in the water, until the river ran red. The river came to be known, until this day, as “Blood River.”

The Boers pulled aside a wagon, and a commando of around 100 men galloped out. Shooting from the saddle, they caused havoc among the Zulus until their forces were divided and routed. The Zulus fled, and the Boers pursued them until dark, leaving around 3,000 Zulus dead on the battlefield, and countless more off the site, with even more dying later from their wounds. Remarkably, there were no Boer casualties to speak of, though Pretorius himself was slightly wounded in the arm, and another two Boers were nicked by spears.

It was truly a miracle, and the Calvinistic Boers gave the glory to God, taking their amazing victory as a sign from the Almighty that He was with them and that just as He had given the land of Canaan to the Israelites, He had delivered Natal to the Boers.

After the battle, Dingaan fled into Swaziland, where he was subsequently assassinated, and in 1840, Andries Pretorius and a Boer commando unit of around 400 helped Dingaan’s half-brother, Mpanda, establish himself as king. And so it was that the Boers of Blood River made a pilgrimage to Hlomo Amabutu, “The Hill of Execution,” to find the murdered bodies of Retief and his party, and to give them a Christian burial.

It was there that they retrieved the treaty from a corpse untouched by the vultures. The Boers kept their part of the vow, and built a church to God and ever after their descendants have honored December 16 as a sacred day—that is, until the traitor governments of P.W. Botha and F.W. De Klerk (1980s onward) ceased observing it as a public event at the Voortrekker Monument. Even so, there have always been Boers who kept the day holy at private and political rallies.

One hundred years later, in 1938, when the Boers had once again gained power in their own country, they built the mighty Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria to commemorate the Battle of Blood River and the covenant they had made with God. On the lower floor of the massive monument stands a cenotaph to the Voortrekker dead, which from the ground level, can be seen through a circular well in the marble floor.

In the domed ceiling, some 120 feet above, there is a little hole, and at exactly midday on the 16th of December, the Sun shines through that little aperture, down onto the cenotaph, to illuminate the words on it: “ONS VIR JOU SUID-AFRIKA.” These are the words of the South African anthem, “Die Stem,” (“The Call [or Voice] of South Africa”), which pledges our lives for our country and volk. The site of Blood River, too, was graced with 64 bronze, life-size wagons, forming an eternal laager to mark the site of this significant battle, and God’s grace.

However, the defeat of the Zulus, caused the British to cast even more covetous eyes over Natal, and by 1843, British encroachment from the Eastern Cape led to a war between the Boers and the British, with the Boers besieging Congella. The British broke the siege and in 1845, just as the Boers were reaping the rewards of their hard work, the British formally annexed the Republic of Natalia, claiming that the Boers were still British subjects and as such any land they claimed belonged to the Crown. Once again, the Boers became disheartened, having sacrificed so much, only to find themselves once again under British rule.

However, it was the Boer women who vowed that their beloved dead husbands, fathers and sons, and all those at Bloukrans, should not have died in vain. Even if they had to cross the Drakensberg range barefoot, they would do so, but they would never remain under British rule. Heartened by the courage and the willingness of their women to endure further sacrifice, the Boers trekked once again over the Drakensberg Mountains into the fledgling republics in the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. There they were to achieve independence until the discovery of gold in the Transvaal brought an unholy alliance of bankers and gold mine owners to threaten their sovereignty—yet again.

Endnotes:

1 Animism is a category of religion that does not accept the separation of body and soul. It is based upon the belief that souls are found in animals, plants, stones and other objects. Many animists teach that there is one supreme god (who may be relatively uninvolved in everyday life) and many lesser gods. Animals are worshiped as earthly representatives of the gods.

2 During the 17th century, a migration took place that led thousands of Negro people from southern Zaire in various directions to cover much of sub-Saharan Africa. One of the tribes who took part in this migration was the Xhosa, descended from a clan of the Nguni (Zulu). Some Xhosas, however, are descended from the Khoisan people, and the Xhosa language differs from Zulu in that it has click sounds derived from the Khoisans. The Xhosa tend to dominate politics in South Africa. Presidents Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki are Xhosan.

Article Source: BarnesReview.org

More on the Battle of Blood River:

The Day of the Vow

“The Day of the Vow was a public holiday held in South Africa before 1994. The day was observed as a religious holiday by Afrikaners in memory of the victory of the Voortrekkers over the Zulus at the Battle of Blood River on 16 December 1838. Before the battle, the Voortrekkers took a vow to observe a day of thanksgiving should they be granted victory. This video footage consists of life-size bronze replicas of the wagons involved in the historic battle of Blood River.”

The Battle of Blood River Monument